- Home

- About The Far North Line

- Contact

- Documents

- Rolling Stock Needs in Scotland - 2017Aliona Report by Tony GlazebrookFoFNL Submissions and ResponsesLevel Crossings Articles by Mike Lunan

The Friends of the Far North LineCairdean Na Loine Tuaththe campaign group for rail north of Inverness - lobbying for improved services for the local user, tourist and freight operator

The Friends of the Far North LineCairdean Na Loine Tuaththe campaign group for rail north of Inverness - lobbying for improved services for the local user, tourist and freight operator- Home

-

FoFNL Home

Search the Site

FoFNL Aims

JOIN FoFNL NOW

About The Far North Line

Special Offer! Highland Survivor by David Spaven, £9.00 inc UK P+PPurchase FoFNL

Magazine BacknumbersVisual Guide to What You Can See From the TrainAudio Guides to What You Can See From the TrainStrathclyde University ReportAliona Report by Tony GlazebrookOur Constitution Find us on Facebook FNL Timetable Railway Acronyms Selection of Useful Rail Documents Out & About on the FNL Geographical Note E-mail FoFNLCompanion Pages to Magazine Issues From May 2020 Onwards

- › Newsletters

- › Archives

-

Late-running and Cancellation StatisticsLinks to 2005/6 FoFNL Documents Old Press Releases Old News Letters Open Letter to Franchise BiddersFoFNL Submissions and Responses

- › AGM & Committee Minutes

- Committee, 10-05-19, Inverness Committee, 24-10-15, Alness Committee, 12-04-15, Alness Committee, 08-01-15, Inverness Committee, 27-10-14, Alness Committee, 21-07-14, Inverness AGM, 31-05-14, Conon Bridge Committee, 07-12-13, Edinburgh Committee, 07-09-13, Inverness AGM, 03-06-13, Thurso Committee, 16-03-13, Edinburgh Committee, 08-12-12, Inverness Committee, 08-09-12, Edinburgh AGM, 11-06-12, Dingwall Committee, 18-02-12, Inverness Committee, 21-01-12, Edinburgh Committee, 22-10-11, Edinburgh AGM, 18-06-11, Wick Committee, 26-03-11, Edinburgh Committee, 30-10-10, Inverness Committee, 24-07-10, Edinburgh AGM, 31-05-10, Inverness Committee, 31-05-10 Committee, 06-02-10 Committee, 31-10-09 AGM, 27-07-09, Helmsdale Committee, 18-04-09, Inverness Committee, 13-12-08, Tain Committee, 15-08-08, Inverness Committee, 29-03-08, Kirkcaldy Committee, 08-12-07, Tain, Committee, 25-08-07, Helmsdale

- › › Local Services

- Accommodation Shops & Services

- › › 1998

- › › › February

- A View From The Signalbox Chairman's Welcome Railway Centenaries Railway Cuttings Get Steaming Annual General Meeting 1997 New Service from Dingwall Two Letters

- › › › June

- A View From The Signalbox Steam Through The Highlands Highland Festival Summer Timetable Review Steam Train To Kyle T(r)ain Locomotives Facing Points Cycling Matters Books For Sale Committee Matters Railway Cuttings

- › › › October

-

A Day Of Contrasts - Editorial

Steam Today - Traffic Tomorrow

Steam Timetable - 10th October 1998

Annual General Meeting 1998

Committee Matters

Missed Opportunity & Cycling Matters

Sunday Service - Please

Did You Ever Want To Become An Engine Driver?Books For Sale Facing Points Railway CuttingsScottish Association for Public TransportRailtrack Consultation Passenger Services For Easter Ross

- › › 1999

- › › › January

- 125th Year Membership Renewal Annual General Meeting 1998 Facing Points Freight - Lovat Pride Thomas the Rhymer Steam In The North 1998 Committee Matters Shin Viaduct Footbridge Railway Cuttings South & East Sutherland Local Plan The Inverness Question Letters

- › › › June

-

View From The Signalbox

Comment

Obituary for Harry Miller, founder chairman of FoFNLService Provision Letter to The Editor Facing PointsSubmissions to Highland Rail DevelopmentsRailway Cuttings Bustitution 125th Anniversary Events Dornoch - An Alternative PerspectiveTransport Policy for a Sustainable Scotland

- › › › October

-

View From The Signalbox

Annual General Meeting 1999

North Railway Line - 125 Years (i)

125th - the day

Railway Cuttings - 25 years ago

Facing Points

Letter to The Editor

Has the Beauly project hit the buffers?

ScotRail price cuts

Watch this space! Safeway Freight to CaithnessAbout 80 miles to the Insch Fund Raising

- › › 2000

- › › › February

-

Into The Millenium

More On The 158s

125 Years On The North Railway Line (Part 2)1999 Annual General Meeting Committee Matters Highland Railway Heritage Railtours View From The Signalbox Dates For Your Diary From Your Secretary's Desk Facing Points Trailing Points Diamond Crossings Railway Cuttings Overnight Train Services Campaign for Borders Rail Learning By Rail

- › › › June

-

Front Page

View From The Signalbox

Summer Service

Facing Points

Scottish Highlands Rail Festival 2000

125 Years on the North Railway Line (Part 3)Rail Users Consultative Committee For ScotlandTransport Specialist Joins The CommitteeVolunteers Required Photographic Competition Letters to The Editor Scotscalder Station

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Three Steps Forward - One Step Back

Annual General Meeting 1999

ScotRail Hits the Buffers

'Times - They Are A-Changing'

The New Generation - Turbostar

James Kennedy HR Models

Facing Points

Fort Augustus Line

Photographic Competition

ScotRail Takes to The Road

Overnight Train Services

Letter to The Editor

Tain Commuter Train Publicity

Letter to The Editor - Modern Railways Magazine

- › › 2001

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Notes From the Chairman

AGM 2000

View From The Signalbox

Tain Commuter Passenger Survey

Facing Points

Re-opening of Beauly Station

TPO Van at Dingwall

Strategic Priorities - Scotland's RailwayIn The Aftermath of Hatfield Photographic Competition Abandoned New Committee Appointees

- › › › June

-

Front Page

Crisis Point For The Friends?

Response To Scottish Executive Consultation PaperAlness Station Clean Up Railway Cuttings ScotRail Press Releases Highland Railway Society View From The Signalbox Facing Points Centenary Of The Mallaig Line Far North Video 125 Offer Shunting CompetitionAnd We Thought We Were The Best Of Friends With ScotRail!

- › › › October

-

Front Page

Growing Far North Traffic

Annual General Meeting 2001

EWS - Rail Freight on The Far North LineEWS and ScotRail Press Releases Facing Points Coming Up With The Goods Subscription Rates The Dornoch Bridge Revisited Promoting The Far North Line Letters To The Editor Passenger Watchdog Meets Freight On The Far North Line

- › › 2002

- › › › February

-

Front Page

Freight and Passenger Developments

Annual General Meeting Report

Facing Points

Membership Renewal

Committee Meeting Report

Sheep and Trees

Carved Stone Head

Getting Familiar With The Far North

Reminiscences of Muir Of Ord

Railway Cuttings

Clachnaharry Road Bridge ReplacementFree Ticket Offer Winter Sunday Service to Wick Highland Railway Heritage Far North Freight Summary Strategic Rail Authority Letter from David St. John Thomas

- › › › May

- Front Page Beauly Station Re-opening Beauly Timetables - Present and Past More About Beauly Letting the Train Take the Daily Strain Delivering the Goods Correction - Lorry Miles Dornoch Unlooped Dounreay Waste Beauly Station (Ross-shire Journal) Facing Points Far North Future Alness Station Memories Announcements RSPB Reserve at Forsinard Letters to The Editor

- › › › October

-

Front Page

Developing & Holding Traffic

AGM 16th November 2002

Committee Matters

Taking The Iron Road

Northern Timber By Rail

Five-Year Rail Service Blueprint

Facing Points

Muir Of Ord Station Update

Death In The Far North - Dornoch Closure 1960Royal Train Jubilee Visit To Train Or Not To Train? Adding To A96 Congestion "Broken Rails" Sleepers - Now And Then Kinbrace Open Day Highland Rail Partnership Forsinard - A Day Out Striking Gold In Helmsdale

- › › 2003

- › › › January

-

Front Page

2002 - A Good Year for The Far North LineAGM - 16th November 2002 Railway Journal Back Numbers Committee Reports New Appointment for Frank Roach Comfort Complaints Carved Stone Head Our Bridges In The North Tain Initiative Group Access Project Facing Points Iron Road To Orkney And Skye Membership ReminderMSP Calls For Better Train Service NorthMuir Of Ord Station UpdateCalls For More Goods To Travel By TrainCoincidences!

- › › › April

-

Front Page

Frank Spaven - An Appreciation

Questions for Scottish Election CandidatesTrain Service Aims For 2004Jellicoe Express Commemorative PlaqueHighland Deephaven Planning Saga Good News On Rail Freight Links Inverness Rail Heritage Facing Points Trondheim! - No Comparison New Rôle For Old Railway Building Highland Railway Heritage Membership Committee Meetings - February 2003 MacPuff Car Badge

- › › › October

- Front Page Northern Rail Future AGM 15th November 2003 Traffic Surveys Facing Points Railways Bleeding To Death Commuter Concerns Destination Invershin ScotRail Press Release Dornoch Firth Crossing - Again Obituary for Archie Roberts News - 1878 Far North In Print Milburn Freight Yard Survey Committee Meeting Reports

- › › 2004

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM 2003

Rail Passengers Committee Scotland

Membership Matters!

Small Town Networks Conference, SwedenSRA Hearing View From The Signalbox Freight Flow Estimate 2003Railfreight On The North Line - A Rising Star?Car Park Clue To City's Rail Heritage Iron Roads To The Far North & Kyle Committee Meetings

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

The Case for Rail in the Highlands & IslandsRailfreight on the North Line - A Rising Star? Part 2Summer Excursion A Cycling Family's View of the LineWorking Together to Build a Better RailwayEditor's ApologyThe Highland Scots Become Interested in RailwaysSeen By Many, Visited By Few Membership Matters Facing Points Letters to The Editor Community Rail Development Press Report

- › › › September

- Front Page Headcode AGM Policy Aims for Future Rail Services Gold Panning... Facing Points Inverness-Aberdeen Line The First Group ScotRail Franchise Train Times For Lairg Dornoch Bullet Train? Scottish Rail History Book Review Committee Meetings

- › › 2005

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM 2004

Rail Passengers Committee

The Future of the Regional Train

The Law of Unintended Consequences

Class 158 DMUs

A Rural Freight Revival?

Facing Points

Widening Clearances for Freight ContainersWinter Evening Meeting Community Rail Development Strategy Caithness & Orkney Deserve Better Invernet Flying Start Letter to Editor Membership Matters Good News on Apex Fares Committee Meeting Far North Guide Book

- › › › June

-

Front Page

Headcode

A Better Railway For The North

Fearn Station

Rail Passengers' Committee, Scotland

Priceless Peatlands

A Most Convivial Evening

Freight News

Facing Points

Highland railway: People & Places

Our Secondhand Shoestring Railway

The Slow Train

Summer Outing to Dunrobin

Kennedy Highland Railway Models Trust & The Nairn Museum

- › › › September

-

Front Page

View From The Signalbox

Association of Community Rail PartnershipsOpportunities From The New TimetableHighland Rail Partnership Connections With Orkney Ferries Tain Station Back On Track Dunrobin Locomotive Dornoch Rail Link Facing Points Freight Facilities Grants Membership Statistics

- › › 2006

- › › › January

- Front Page Headcode View From The Signalbox Well Done Frank A User's View of Invernet New Timetable, December 2005 Morning Session of 2005 AGM Pen Pictures A 'Knight' Dons Its Armour Submissions Announcements Facing Points

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM 2006

Volunteers Required

Scottish Executive Consultation on Rail PrioritiesDornoch Rail Link Some Thoughts from the Lairg LoopKeiss Primary School Pupils Head For PitlochryRolling Stock Improvements Possible Steam Train Service June 2006 Timetable Making Tracks For Lonely Altnabreac Cab Ride Committee Meeting 25th Feb Savings on Group Travel

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM 2006

Timetable

Future Prospects for Rail in The North

Really Useful Rolling Stock

SQUIRE - Service Quality Incentive RegimeLetter to The Editor Book Review Cab Ride - Part 2 Alness Station Steams AheadMeeting the Community Councils - CreichSummer Excursion Committee Meeting 27 May

- › › 2007

- › › › January

- Front Page Headcode Controlled Emission Toilets Response to Network Rail Consultation Lentran Loop Regional Transport Strategy The RETB Story Scotland's Expanding Railways AGM 2006 Speakers Membership Matters Letter to The Editor Letter to The Editor 2 Committee Meeting 26 August Books

- › › › June

- Front Page Headcode Notice of AGM 2007 FoFNL Convener Appointed to RIAC ScotRail Customer Forum Donation Freight RUS Consultation Response Kessock Bridge Logjam Facing Points Centralized Traffic Control Signalling Letters to The Editor View From The Signalbox OV-fiets - Dutch Train Bike Hire Georgemas Chord Technicalities Committee Meeting Minutes 9-12-06 Committee Meeting Minutes 22-03-07

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

The Process for Change on the Modern RailwayGovernment - High Level Output SpecificationMore Caption Suggestions The Lentran Loop Class 158 Refurbishment AGM 2007 Speakers Convener's AGM Report - 2007 December 2008 Timetable Bothered by TLAs? AGM 2008 and Winter Evening Social Committee Meeting Minutes 26-05-07

- › › 2008

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

Review of Highlands Rail DevelopmentsTimetable: Technical Overview Track PatrollingMega Trucks Coming to a Road Near You Soon?Tesco Considering Rail Transport More Abbreviations and Acronyms Slow, Snow, Block, Block, Snow New High Speed Train for ECML Freight News "Dunrobin" Emigrates Four Minutes MoreHighland Railcards Recognised by TVMsSponsored Walk May 9, 2008 AGM Activities AGM 2008 Committee Meeting Minutes 25-08-07

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Invernet Triumph(s)

National Planning Framework For Scotland 2FoFNL Committee Visit To Kirkcaldy And DunfermlineStation Survey Slow, Snow, Block, Block, Go! Winter TalkTransport Connections In The Highlands 2008 (Part 1)Facing Points Trains Which Are Never Late Highland Railway Loops Committee Minutes 8-12-07 Tain

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Convener's AGM Report

AGM 2008 Speakers

Summary of Station Visits

April-May 2008What Needs To Be Done - Station VisitsTransport Connections in the Highlands 2008 (Part 2)Better Connections Another Acronym December 2008 Timetable Review Line For All Seasons (Part 1) Winter TalkExcerpts From

"The Railway Magazine"Committee Minutes 29-03-08 KirkcaldyYour New Treasurer

- › › 2009

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Advance Notice 2009 AGM

Headcode

Information Request

Towards a Great North of Scotland Railway2008 Survey of FNL Delays First ScotRail Sponsors Orchestra Line For All Seasons (Part 2)Hare or Tortoise?Winter Talk - Calum Macleod

Strategic Transport Projects ReviewMost Innovative Approach to

Cycle-Rail IntegrationImpressive Growth In Rail Travel NumbersHighland Council TECS Committee 20th NovemberInvergordon Scoops Station Award Reviews The "Jellicoes" by Roger E.G.Read Extract From SLS Journal

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Advance Notice 2009 AGM

Headcode

Diesel the Cat

FoFNL NewsletterMay 2009 Timetable Review

Reaches Heart of Govt.Rail Users GroupKildary Bridge Bash

Issues for HITRANS MeetingSurvey of 09Sutherland Local Plan The Passing of Two Senior Railwaymen Testing the Track to Wick Thumbs Up for Invernet

FNL Delays (Part 1)The "Jellicoes"

by Roger E.G.Read (Part 2)National Archive of Railway Oral HistoryRomantic Snow Blocks

- › › › September

-

Front Page

View From the Signalbox

Headcode

Strengthening The Far North Line

Letter to Transport Scotland

The Helmsdale Station Project

Punctuality Best in a Decade

The Level Crossing Hazard (Part 1)

British Transport Police

Pedal For Less at Inverness

Parry People Mover Class 139

Railway Self-Sufficiency

New Freight Service on the

Highland Main LineJubilee Refreshment RoomsAGM Speakers

Sowerby Bridge StationThe Line In Photographs:Extract From Railway Magazine

Book Review

- › › 2010

- › › › January

-

Front Page

View From The Signalbox

Headcode

Highland Wide Local Development Plan

Railfreight Scotland Policy ConsultationThe Level Crossing Hazard (Part 2)ForsinardMemo to FoFNL Committee

Lonely Yet Fascinating OutpostScotland RUS Generation 2Accolade for ScotRail and the RSNO Two Bridges to Farr (and Evanton etc)

Scoping ExerciseUpdate on Progress at Helmsdale StationThe Far North Line During WW2 Obviously a Peak Christmas Saturday! Extract from The Railway Magazine

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

In The Beginning

A Day In The Life...

British Transport Police Report

A Future For The Highland Lines

A Siding We Built In A Week

A More Prestigious Train

Sample Covers

Necessity Mothers RETB Reinvention

The "Twa Brigs" And Freight

Station Usage

Extract From "The Railway Magazine" 1933Letter To The Editor

- › › › September

- Front Page Headcode Level Crossings - Part III Book Review Contribution to Level Crossing Debate Campaigning for Conon Station Press Coverage for Conon Station AGM 2010 Speakers Question to Members The "Twa Brigs" and Freight - Part II Far North Line Station Anagrams 2010 AGM Convener's Report Letter To The Editor Ross-shire Transport Forum Vacancy for Newsletter Editor

- › › 2011

- › › › January

-

Front Page

2011 AGM Notice

Headcode

Contribution to Level Crossing Debate

RAIB Report on Halkirk Level Crossing CollisionRAIB Bulletin About Dingwall DerailmentSubmission to Network Rail on Scotland RUS (Generation Two)Timetable Proposals Inverness - Dingwall Line Capacity Dunrobin - Locomotive and CastleInverness Depot

Scotrail Team of the Year AwardSetting the Points in the Right DirectionHighland Council's Approach to Level CrossingsFrom the Newspaper Archives Book Reviews Railtour to Wick

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Letter to Editor

AGM Notice

John Duncan

Headcode

Response to RUS2

Mallard Comes To The Rescue

Rail Station Now On Track To Re-Open

Scottish Parliamentary Elections

Let's Get on With the Work!

Far North Line Patronage Continues to GrowHow Far Away is Aberdeen or Even Dalcross?Touring On and Around the FNL Acronyms The Journey to Nowhere Bradshaw - Brad Sure? Pen Picture of Potential Editor In Days of Yore

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Editorial

Headcode

Library Legalities go to Appeal

In for a Shilling, In for a Pound?

FoFNL AGM, 18 June 2011, Report

Gladstonian Daftness?

Convener's Report

Kessock Chaos Partially Averted

FNL Train Loadings

Level Crossings - Road-Rail vs Road-RoadLevel Crossings - Part IV The RUS Rolls On Through to Orkney by Taxi Taking a Cab 'Tain't arf confusing at Inverness...' Farthest South-East to Far North-East East Coast Meals Not So Hot Bookworm's Burrow Connections Financing and Franchising Potential Highland Freight Improving Far North ServicesNew Stock for Invernet and the Far North Lines?

- › › 2012

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Letter to the Secretary

Headcode

Keith Tyler (1930-2011)

Yet more Forward Planning Reports

Future Plans are No Plans

Piping more freight on to the Far North Line?Touring around the Far North Line Whither the Far North Line? (Re-)Turning the Tables A Load of Hot Cold Air A Highland Winter Refreshing News Recollected in Tranquillity Branch Lines Too Close? We Await the Time

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Rail 2014 Consultation

Level Crossings - Part 5

Future Rolling Stock Policy in Scotland

Caledonian Sleepers

"Black Fives" in the Highlands

Nucleating Georgemas

The new Highland Main Line Timetable

Connections from the Far North Line

What Railway Lines? There's Snow Lines There!Station Usage Statistics Bad News for CulrainConon Bridge Station Could be Opened SoonPress Release - Inverness Caledonian SleepersWish You Were Here - Postcards Recent HITRANS Reports Snippet of History Your Trespasses Will Not be Forgiven Book Review - Trainspots Motorail Highland Chieftain Northbound Far North Freightliner Keith Tyler's Farewell

- › › › September

-

Front Page

A Quotation Whose Time is Awaited

Headcode

2012 FoFNL AGM, Convener's Report

FoFNL Conference, Dingwall, 11 June 20122013 AGM and Conference C'mon Conon!Rail Matters to Muir! "The Great Train Day"Highland Main Line Letter to The EditorA 1932 Perspective of The Far North LineFar North - Forty Years On Can Level Crossings Ever Be Safe? Scottish Railway Coats-of-ArmsFar North Line Past, Present and FutureOn The Road To Beauly and Back Via Beaulieu RoadHistory is a String of Broken Hopes Yestermonths in Parliament

- › › 2013

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

December 2012, Timetable Revision

Station News

Franchise News

Rail Fares

2013 AGM and Conference

Far North Line Upgrades

Committee Meetings

Far North Line: Past, Present and FutureRoom For Growth - A Reflection Four Years OnContributions Freight on The Far North LineStaff at Conon StationLevel Crossings - Part 6 Book and DVD Reviews Yestermonths in Parliament

in Highland Railway Days

- › › › April

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM and Conference

Conon Bridge: The Day Dawns at Last!Fares News Station Usage Figures Contributions FNL Train Service Enhancements Conon to Cromarty Corridor Do They Mean Us? News From the Central Belt High Speed Rail: Anything For Us?Frank Spaven and the Development of Railways in ScotlandWell I'll Be Blowed! Problems on The Kyle LineFar North Line: Past, Present and FutureLetter to The Editor Book Review Yestermonths in Parliament

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

2014 AGM and Conference

Report of FoFNL Conference: Monday 3rd June 2013Franchise News The Swing of the Pendulum FNL Train Service Enhancements Fares News News From the Central Belt Progress (Of Sorts) on The HML New Life for Helmsdale Station House May We Have Our Tracks Back Please? Level Crossings - Part 7 Caption (Non-) CompetitionMaking Rail Freight Work for the HighlandsOvernight Train, Two Capitals and a Castle...Letters to The Editor Getting to GRIPs Yestermonths in Parliament Contributions

- › › 2014

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM & Conference

Inner Moray Firth Proposed Development PlanFar North Line Train Service EnhancementsHow Inverness Could be Closer to the Central BeltRETB Renewal Food For Thought? Helmsdale Comes Back to Life - Part 1 Franchise NewsNetwork Rail's Enhancements Delivery PlanIntercity Express Project News From the Central Belt High Speed 2 and Scotland HML Train RunningWhy Long Single-line Railways to Inverness?Level Crossings Part 8: An InterludeInverness Set for Showdown - 50 Years OnCorrection Yestermonths in Parliament Contributions

- › › › April

-

Front Page

Headcode

Changes at Network Rail

Station Usage Figures

ORR Final Determination

FNL Train Service EnhancementsAberdeen - Inverness Upgrade Plans Issued At LastNew Railcard Highland Rail Vision News From the Central Belt Franchise News Grub Steak? Unfair Fares for Highlanders Helmsdale Comes Back to Life - Part 2FNL Golden Jubilee 1963 - 2013: From Long-term Decline to Resurrection?Collapse of River Ness Rail Bridge Contributions Obituary - Alastair McPherson Book ReviewDid You Ever Want to Become an Engine Driver?Yestermonths in Parliament

- › › › October

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial - View From Afar

Secretary's Introduction

Abellio Awarded ScotRail Franchise

First ScotRail Letter to FoFNL

ScotRail Response to FoFNL ComplaintsNetwork Rail Control Period 6 FoFNL Policy DocumentFoFNL Conference Report Months of Misery Inverness Ticket Barriers Highland Main Line Update Inverness - Aberdeen Line Progress The Highland Railway Survey 1994David St John Thomas - An AppreciationIain Shand - FoFNL MemberHelmsdale Station House - Official OpeningCulrain for Carbisdale Castle Steaming to Dunrobin and WickArdgay Station 150th Anniversary CelebrationMy First Far North Line Journey Book Review

- › › 2015

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

AGM Advance Notice

No More Cancellations!

Branchliner - Timber From Caithness & SutherlandNetwork Rail CP6 FoFNL Policy Document Part 2Note From First ScotRail December 2014 Timetable Review Press Coverage Punctuality Pleases Passengers Faster From Fife Collision Course Averted Highland Main Line Update Caledonian Sleeper FranchiseInverness - Aberdeen Line ProgressThe New East Coast Franchise Before Our Time Station Usage Figures FNL Electrification FNL Signalling Club 55Trust Me, I'm Your Tour Manager! - Book ReviewRadio Extends Times at BroraInverness - Thurso, An Australian Traveller's PerspectiveAn Afternoon in Altnabreac Permanent Way? Yesteryear at Dingwall North Ness Viaduct Collapse 1989 Shadow Ministerial Appointment Yestermonths in Parliament Restoring Railway Clocks

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

Letter from Steve Montgomery

Submissions to Holyrood Freight InquiryHML Freight and Electrification Finnie Wins Support for Far North LineSTOP PRESS! From Infrastructure Questions May 6thScottish Parliament Written AnswerScotRail Breakdowns to be Halved by AbellioWe Love OUR Trains May 2015 Timetable UpdateAbellio and Network Rail AllianceTrain Metamporphosis Inverness - Aberdeen Update Transform Scotland News Release Two Summits Brora Station Building Letters to the Editor More Letters A Cold Journey to The Far North HITRANS News UpdateRailways in the Highlands: Improving the Model for the FutureA View From the Sidelines Back to Banff FoFNL Members' Visit to AltnabreacGoing Dutch - A New Rail Cycle in the Far NorthDouble Dutch DictionaryUp Many a Creek With Scores of Paddles - Book ReviewTina's Tearoom, Dingwall Station Highland Railway Sesquicentenary Miscellany

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

Minor Details

Newsletter No.40 Revisited

2015 AGM

Thurso Heritage Society Website

New Trains in Scotland

Defibrillator for Inverness StationLine and Rolling Stock Updates Inverness - AberdeenTemporarily Permanent Speed RestrictionHITRANS FNL Progress Report HITRANS BranchlinerFaster Service Between the Highlands and Edinburgh in Jeopardy?Train to Black Isle ShowThe Question of the Refurbished 158sLunatic Line Transport Focus Events Sept 2015 Book Review Letters to the Herald FoFNL Conference 1995 - 20 Years On Lentran Long Loop Request Stops Fond Memories of the Coffee Pot Two Far North Projects Lesson From The Recent Past Invergordon Opportunity ABC on the Far North Line Stations NewsParliamentary Questions and AnswersDVD Review

- › › 2016

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

FoFNL Submission to Transport Scotland Railfreight ConsultationDavid Spaven - Railway Atlas of ScotlandFar North Blockade Far North Line Update Highland Main Line Update Inverness - Aberdeen UpdateHITRANS Rail Stakeholder ConferenceStation Usage Figures 2014-15 Stations Survey 2015Summary of FNL Station Visits - August 2015Summary of Inverness Station Visit - August 2015Model Railway: Culrain Station in 1960Interesting Question...The Urgent Need for the Lentran Long LoopScotRail Signs Up to Town Centre First PrincipleViewhill House Restoration Project Trackwalker 2016 AGM Book Reviews Helmsdale Station Update Parliamentary Questions and Answers ...and Finally

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

Your Committee

Far North Line Update

Caithness - Edinburgh Sleeper

Scotland Route Study - FoFNL ResponseBook Review Parliamentary Questions Serco Class 73s Travel North Highland Main Line Update Delivering the Goods Dual Tracks!Campaign for Better Transport Challenges CSRF ReportGeorgemas Railhead Could Benefit Caithness EconomyInverness - Aberdeen UpdateStorm Damage on West Coast Main LineTransport PolicyEffective Representation for Rail Passengers: a loss of Focus?The Economic Contribution of Rail in ScotlandBikes on Trains New Far North Line History John Thurso to Chair VisitScotlandA Railman RemembersFranchise Rules What If...? Properties For Sale

1 - Stumbling Upon a Job

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode and Conference Report

Editorial

Worst Ever Far North Punctuality?Subscription Rates FoFNL Email ChatterFoFNL Response to HITRANSScotland Route Study - July 2016

Regional Transport Strategy RefreshTransport Focus National RailVerster Visit

Passenger Study, Spring 2016Level Crossings - Part 9:Far North Line Update Highland Main Line Update Inverness - Aberdeen Update Inverness Station Upgrade Parliamentary Questions Far North Line in the Press Letter to the Editor Rail Freight - Planning Ahead BaDAG in the News

Some Odds and EndsSwiss Rules - Letter From a MemberNo "Day Returns" From Culbokie A Railman Remembers, Part 2The "Cycling Scot" Visits AltnabreacForsinard Lookout Tower Caithness Archive Centre

- › › 2017

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM

Editorial

Four Meetings and a Result!

More Email Chatter

Rail Infrastructure Strategy ConsultationFoFNL HLOS 2017 Submission Level Crossings - Part 10: Update Parliamentary QuestionsWick Man Keeping Far North Trains On TrackStation Usage Figures 2015-16 Evanton Station Proposal Cow Strike!Time Is Now For Fit-For-Purpose Rail NetworkHigh Time the HML Was Soaring AheadHML Update Inverness-Aberdeen Update A Railman Remembers, Part 3 Book Review Police Officer to CouncillorDingwall Regiment Soldier HonouredA Station Clock Returns to HelmsdaleThe Battle of Jutland: The Orkney PerspectiveOrcadian Railways

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

AGM Notice and Proposed AmendmentFNL Punctuality Statistics The Far North Line Review Team Cruise Mission Impossible?Rail Infrastructure Strategy Consultation ResponseRailway Policing (Scotland) Bill New Alliance Managing Director Nursery Learning Journey ScotRail HSTs Caithness Sleeper Rails By Sea Lairg Oil Train Demise Highland Mainline Update Inverness-Aberdeen Update Level Crossings Update - 11Transforming Train Travel North of EdinburghReform Scotland:SunRail A Railman Remembers, Part 4 Jellicoe Specials Centenary

Bolder Vision NeededBook Review - Scottish Region Engine Sheds

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

A Guide to the CP6 Funding ProcessLet's Hear It for Transport ScotlandLetter to The Herald Green Thoughts from Railfuture HML & Inverness Station Updates Inverness - Aberdeen UpdateRail Freight's Role in Tackling Climate ChangeInverness: 'Somewhere in the South' Alliance News Level Crossing News Caledonian Sleeper NewsThings Can Only Get Better (Who Said That?)Rail & Sail to OrkneyBook Review - The Insider Rail Guide - Inverness to Kyle of LochalshWhat is a Tourist Train? In the WorksAberdeen to Inverness: Memories of the Resources ManagerAll The Stations Jellicoe Express PlaquesA Railman Remembers, 5 - Thanks Mr PostmanScotland's "Big Sky Country"

- › › 2018

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

Editorial

Best Newsletter - Railfuture Gold AwardPandora Has a Look in the Too Difficult BoxThe Highland Main Line - A Caged Tiger Which Needs ReleasedHighland Main Line Update(d), Nay Modernised?Inverness - Aberdeen Update Parliamentary Questions Station Usage Figures 2016-17 Passengers First... Level Crossings Latest Jellicoe Express Plaques Rail Freight Prospects and Benefits Freight Modal Shift Thrumster Station Honours Tourist Train Concept 1959Inverness: 'Somewhere in the South', Part 2Far Away But Maybe Not So Different Caithness Narrow GaugeA Railman Remembers, 6 - Shunting With CareBook Shelf AGM 2018 Helmsdale Station Award

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM & Conference 1st June 2018Pandora Has a Look at the Laws of PhysicsReview Team Report Level Crossings - 12 Update Book Notice Parliamentary Questions Snow Problem Ardgay - Golspie 150Transport Scotland Workshop ReportPeter Moore - North Highland PhotographerHSTs Are Coming Serco Stock Arrives in Scotland Midnight Train to Georgemas Inverness-Aberdeen ImprovementsHITRANS Rail Stakeholder Conference, January 2018Grasping the Opportunities Find Us On Facebook Climate Change and Modal ShiftRail Could Take the Strain Off Our RoadsWe Need to Push More Freight Onto RailwaysInverness: 'Somewhere in the South', Part 3Dunrobin's SistersThe FNL and the Highland League Football SupporterCulrain Station Brora Station Timetable Out of TimeAnother Overseas Comparison : Vancouver IslandA Railman Remembers, 7 - The Music StationTransport Focus Pipes to Georgemas The Peffery Way Return of the JDI? Sea Defence Repair

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Bob Barnes-Watts

AGM & Conference Report

Praise for ScotRail Conductor

ORR 2018 Periodic Review

Review Team Meeting

FoFNL Press Releases

Inverness - AberdeenFar North Line Update Inverness - Aberdeen Update HML Must be Able to Compete With A9 Fiery Train Barmouth, a Lesson From Wales? Freight Failure Network Rail Devolution

ImprovementsBTP and Police Scotland Merger on HoldGeorgemas Pipe Trains Parliamentary QuestionsRural Economy & Connectivity CommitteePassenger Rights Pandora Looks South Cruise Ships and TrainsLevel Crossings - 13: Just In Case You Were WonderingTimetable Chaos Platform 1864 Award Class 153 Conversion Something to Think About The Garve & Ullapool Railway (Part 1) Article Inspires Memories Kildonan Station Loads of PotatoesA Railman Remembers, 8 - One Potato, Two Potato...Lairg 150 Exhibition Rogart Cairn Highland Railcard Book Reviews

- › › 2019

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

FoFNL 2019 AGM

Remembering Bob Barnes-Watts

Broken Connections

Far North Line Update

Transforming the Highland Main Line: An Urgent TaskInverness - Aberdeen Update Station Usage FiguresBook Review - The Kyle of Lochalsh and Far North LinesParliamentary Questions Greens Call for More Rail FreightA Recent Observation by Our SecretaryVivarail DemonstrationPandora Pokes Around What Lies at the Rainbow's EndGood Work Should Not Go Unnoticed Inverness Station Did You Know...? Points Failure Level Crossings - 14Getting Around the Highlands and IslandsFNL - Wartime Line of Duty The Garve & Ullapool Railway (Part 2)Book Review

Change at BrockenhurstA Railman RemembersThrumster Station

9 - The End of the InnocenceJohn Yellowlees Considers New Zealand RailwaysCharters: “Scotland Open for Business”Steam Dreams - Highlands & Islands Explorer 2019Raildar Inter7City Circle

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Highland Survivor

FoFNL 2019 AGM & Conference

ScotRail Remedial Plan

Clearing the View

Freight Future

Far North Line Investment Is On the Right TrackHighland Main Line InvestmentAberdeen-Inverness Improvement Project£1.6 Million Depot Upgrade Parliamentary Questions New Sleeper Stock Debut Letters to the Editor Not the Buchan Line! Norway Imagination Pandora Opens the Fare Box Technology Advances Determined Effort Strathpeffer Speeding BTP Merger Rail Work Rewarded Final Jellicoe Plaque Unveiled A CRP For the Far North Line?CIS Installations Nearly CompleteDVDs Review: Steam Driver's Eye ViewStay Safe With Network Rail & ThomasInverness Tram Map Bridge Strike Driver Fined Posh Trains to the North? Time Does TransfixCharlevoix: Lovely But Look Carefully

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

2019 AGM - Convener's Report

2019 FoFNL Conference Report

Shuttle

Stuck at Stanley...

Inverness - Aberdeen Update

Control Experience

New CIS on FNL

Active Travel Carriages

Pandora

Caithness Sleeper

BTP Merger Dropped

Inverted Priorities

Inverness Gridlock

Parliamentary Questions

Alex Hynes to Give Keynote SpeechLetter to the Editor Rail Investment Railway Resilience Far North Excursion Article Débâcle PHEW Dingwall Bid Wick Regeneration Brora Station John Melling SFJB Report Truly Transformative Great Scenic Tasting Box A Royal Route Mayflower in MayNess Islands Railway VandalisedA Peatland World Heritage Site?

- › › 2020

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

2020 AGM Announcement

Pandora

Franchise Termination in the Press

Review Team - Final Report

Tony Glazebrook on RT Final Report

Class 153 News

Railfreight - a Key Part of Tackling the Climate EmergencyClimate Challenge Membership Matters Joined-up Transport? Epidemic of Wasted Energy HML Update Inverness - Aberdeen Update Azuma Track Test Parliamentary Questions Travel to the Highlands Caledonian Sleeper Letters to the Editor Inverness Interchange A Railway Terminus on the Moon Dunrobin Progress The Blackbird Sings Deer Leaps Book Reviews

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Pandora

Bob Maclennan - An AppreciationThinking Big in GovernmentStrategic Transport Projects Review 2008...Inverness - Aberdeen Update Parliamentary Questions Towards a Highland HubTime for Timber Trucks to Give Way to TrainsSPICe Spotlight Twenty Years On Station Usage Figures 2018-19 Dealing With Rail Tragedy Cromarty Frustration Weaving the Far North Thread Sources of Power Book Review Disabled Persons Railcard Historic Halkirk Ledger No Book - Review ScotRail Staff Charity Success Sleeper Report WWI Dalmore Branch The Fin Del Mundo Railway From Kashmir to Kinbrace

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

CIS Success

Pandora

FNL Review Team News

Inverness Transport Hub News

Decarbonisation Action Plan

Letters to the Editor - Nordic Lines

Parliamentary Questions

Class 158 - Thirty Years in Service

HML Promises 2006

Dynamic Strategic Planning

Timber Trial

Freight Lines

HIE Misses Rail Emphasis

CO2 Savings Wiped Out by New RoadsTough on Carbon Emissions Inward Investment is Reassuring 150th Anniversaries Churchill Barriers 75th Anniversary Dalmore Mystery Solved Royal Train From Invershin Picturing Scotland Book Review St Valery Remembered Autumn Comes Clachnaharry Swing Bridge Scrubs Supplies by ScotRail

- › › 2021

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

FoFNL Business

Stakeholder Panel Relaunch

Pandora

Lentran Loop - Light at the End of the TunnelGRIP - Richard Ardern Contemplates the ProcessDual the Highland Main LineBorders Railway - Model for RecoveryGlenfarg Route - Cross-Party SupportPut More Freight Onto Rail Timber Trial Notes HITRANS Reports An Act of Reciprocity Book Review - The Northern Barrage Hydrogen Conversion Hydrogen Policy Statement Battery Power Karen Cragg Station Usage Figures Parliamentary QuestionsDelayed Improvements Cause Diversion ProblemsInfrastructure Investment Plan Letter NTS2 Delivery Plan Railway News Delny LX Replacement Brora Rail! Out of the Station Window Organic Opportunity Inverness Airport Station Kintore Station Reopens Bus Planning Kyle Campaign 50 Years On Caroline Travels North A V4 at Thurso? Far North Memories

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Rail For All

Pandora

Rail Freight Reflections

Parliamentary Questions

Retiring VPs

How Did They Do?

News Round-Up

FoFNL Red Wheel

Ronnie Munro - Classic Railwayman

The Opening of the Duke of Sutherland's RailwayRaily Mail Canadian Hydrogen Power Coul Links Again Delny Bridge Aids Evanton Case Change at Inverness New ScotRail Accidental Allegory Driftbusters! To Scotland in the 1950sBook Review - Scottish Highland RailwaysElectrifying Scenic Railways Trains For Tourists Sarah Boyack Talks to CILT Ben Alder - New Build Project

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Pandora Ponders the Future

Pandora Looks to the "New Normal"LNER Steps BackScotland's Railway - The Year AheadKeith Farr ZET Comes to Caithness...?Can the Greens Green the SNP on Transport?Premier Inn Arrives in ThursoThe Highland Council on the Wrong Side of the RoadGreat British Railways Travelling on the Far North Line Parliamentary Questions Sunday StrikesWhen Will the Sun Shine on the HML?Customer-Unfriendly Newton Vindicated Wick Works Kildonan Crossing Replacement The Perils of Bad Handwriting News Round-Up Red Wheel Day Book Review Carbisdale Castle Sold? Corporate Vandalism Norway in the News Channel 5 Goes North

- › › 2022

- › › › February

- Front Page Headcode Stop Press - STPR2 FoFNL AGM 2021 Request Stop Rollout Pandora Leaves Above the Line Parliamentary Questions ScotRail - New Structure HML - New Structure Personalised Pocket Timetables Letters to The Scotsman A Rail Strategy For the North Pitiful Capability of the HML New Bus Strategy Needed Thurso Flagstone Tramway The New HITRANS App for MaaS Caithness History Scapa Flow Museum Expands Pop-up Stalls at Wick and Thurso First HST on FNL? Disaster Averted Altnabreac Achievement Low Carbon Logistics Taking Up the Slack Freight Belongs on Rail Clean and Green Railfreight Flourishes... User Errors - (Level Crossings) Channel 5 Success Station Usage Figures A Railway Too Far Birth of Dalcross Station

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

FoFNL Aims & Actions

Distance Versus Journey Time

Pandora

Dalcross Progress

STPR2

KlimaTicket

Transport and Climate

Parliamentary Questions

Freight Multiple Unit?

Cyril Bleasdale OBE

A New Meaning to Becoming a Stationmaster!Roller Coaster Railway Memories of Borrobol Halt Catering Trolleys Return Local CommunicationThe North's Worst Winter for 25 Years (1955)Ardgay Signal Box: hung, drawn and newly quartered'E Poor Wee Lybster Train Stabilisation WorksBook Review - Scotland's Lost Branch LinesElectrifying Innovation Far North Landscapes

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

AGM 2022 - Convener's Report

AGM & Conference Report

Modern Railways Editorial

Celebrating the Duke's Railway

Pandora

Request to Stop

ScotRail - New Trains Procurement

David Shirres on Hydrogen Trains

Hydrogen Trains Enter Service in GermanyStadler Rail Press Release Parliamentary Questions Cassandra Writes Plus Ça Change Will the Red Light Turn to Green? Electricity Feeder Station Plan Station Survey 2022Getting Value for Money on Rail InvestmentDalcross BlockadeIntegrated Transport in the NetherlandsChiltern Railways: The Inside Story Jim Welsh Remembered Moving On Young Stationmaster Looks Back

- › › 2023

- › › › January

- Front Page Headcode Pandora Fair Fares for Scotland Britain's Railway Passengers Survey Delmore Testing ScotRail Regional Roundtable STPR2 Final Report Station Usage Figures Stewart Nicol New Rolling Stock - FoFNL's View Traction Selection Vivarail HITRANS Rail Round Up Conon Bridge Station 50 Years Ago Lairds in Waiting - Book Review Timber Transport Parliamentary Questions Somewhere Under the Rainbow Castle Finds New Owner Green Roofs Network Rail Ecology Focus Please, Stop the Digital World... Bridge Unfilling Adrian Shooter France Acts on Short Haul Flights Robert Garrow

- › › › May

-

Front Page

Headcode

Pandora

New Ministers

Parliamentary Questions

Highland Main Line Questions

The Welsh Perspective

HLOS Published

Flying in the Face of Modal Shift

Letter to the Editor

We Couldn't Have Put it Better

RETB Improvements

Here At Last! Inverness Airport StationWelcome to Rail Highland Council Opportunity Freight in Scotland Executive Column Stewart Nicol Inverness Hydrogen Hub Opportunity Cromarty Firth Rolling Stock Developments Cairngorm Mountain Railway Coradia in Canada Express Internet LMS 100Book Review - Highland Railway Buildings70 Years Ago Kyle Station Museum

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Save the Date

Pandora

New Airport Station is Emergency TerminusAGM & Conference Report FNL Community Rail Partnership HML Anniversary The A9 Campaign If You Build It They Will Come Transport Stasis Cassandra Parliamentary Questions Vital Signs ScotRail Discussions On Your Bike on the Train Cruise Ship Conundrum Station Timetable Posters Nightmare Averted Fare Comment Plane Speaking Class 93 Orkney Red Wheel Dunrobin Update Manx ConnectionBook Review - The Highland Falcon ThiefRETB Success Great Musgrave FinaleBook Review - The Kyle of Lochalsh and Far North LinesThrumster Electrified

- › › 2024

- › › › January

- Front Page Headcode AGM & Conference Pandora News of Defibrillators Delny Bridge Cancelled A Question of Capacity and Ambition Strung Along? View From the Soapbox Road to Ruin HS2 Beheaded Parliamentary Questions Station Usage Figures Notes From the Far North Line Not As Easy At ABC Bike Stands Lottery Dunfermline Customer Service Centre Longitudinal Timbers Renewals Bridge Refresh Miranda Cottage Jamie's Journal Electrifying 'News' Cruise Ship Comments Caledonian Sleeper Experience Bus Experiment Michael Field Video Productions

- › › › May

- Front Page Headcode Pandora FNL 150 FoFNL AGM & Conference FoFNL Committee Meetings Reports Cancellations Inverness Info Cycle Storage Upgrades Why Are We Members of FoFNL? Newspaper Exchange John Macnab Scotland's Railway Delivery Plan Stop Press Moving On From Your Overseas Correspondent Trainline Travesty Altnabreac Parliamentary Questions Class 197 Fair Fares Eventually? A9 vs HML Highland Autobahn Wick in Wartime An Early Royal Visit to Thurso Letter to the Editor

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Far North Line 150th AnniversaryPandora FNL 150 - Forsinard AGM & Conference 2024 Membership MattersHigh-Speed Internet on the TrainSuperfast Trains? I7C Units To Be ReplacedWill the Red Light Turn to Green?Cassandra Discontinuous ElectrificationLong-Term Decisions Needed NowParliamentary Questions Timber Trains Approaching Witches' Hats Anne-Mary Paterson Beauly Express No More Rail Mail News & Views Introducing SCOTO Bilbster Family Quest World Heritage Site Book Reviews

- › › 2025

- › › › January

-

Front Page

Headcode

FoFNL AGM & Conference

HST Replacement

Ticket Office Hours

FoFNL Committee

Cassandra

Parliamentary Questions

Discontinuous Electrification

The Case of the Far North Line

Highland Council Passes Rail MotionMalcolm G. Wood John Allison High Speed Internet on Trains 27 Years of Progress Inverness Signalling Centre Altnabreac - Not Yet... Transform Report Press and Railways A96 Corridor Review Lord Hendy on GBR UK Transport Secretary on GBR Station Usage FiguresPark and Ride Difficulties at InvernessMarking the 150th Happy 150th Wick Station! The King Visits Helmsdale Repurposing Coal Wagons A Winter's Tale...

- › › › May

- Front Page Headcode 2025 AGM & Conference Pandora Later Evening Services FNL Track Renewal Fast Broadband Approaching Angus Stewart Forty Years of RETB Scotrail 1985 RETB Pamphlet Mystery Value of Rail Timely Reminder to MSPs Political Support Scotland in a Siding Railways Need an Overhaul Letters to the Press A Railway Fit for Britain’s Future A Tale of Two ScotRails BWC 3 - The Far North Altnabreac Lament

- › › › September

-

Front Page

Headcode

Holyrood Cross Party Group on Sustainable TransportAGM & Conference 2025 The Highlands Railway Deficit RAIL Magazine Letters Money No Object Parliamentary Questions Satellite Broadband Battery Train Distance Record Cassandra Danger to Life Beneficial Blockade Mind the Gap Wheels of Change Brora Success Story Golspie "Mystery" A Nuclear Future for the North Line Fearn Station in Gauge 1 From The Traitors to Downton Abbey Book Review

The Far North Line - A Brief History

"Land of Mountain, Moor and Loch", and "Land of Mountain and Flood" are phrases which have long been used to describe Scotland and these descriptions are no more appropriate than when applied to the lands to the North and West of Inverness. Not only is the scenery among the most beautiful anywhere, it is also extremely rugged and desolate and supports a very low population base. If it is surprising that a railway was built at all in such difficult and inhospitable circumstances, that it has survived into the 21st century, despite being under constant threat of closure is truly remarkable.

In the face of these difficulties a number of schemes for an extensive rail network in the area were formed in the middle part of the 19th century, and it has to be said that several of these were borne of misplaced optimism rather than commercial reality. It appears extremely unlikely that the shareholders would have provided the necessary financial backing for such proposals. Railway interest in the Northern Highlands therefore fell into three categories: those lines which were built and are still open, those lines which were built but which have since closed and those lines which did not get past the planning stage.

The backbone of the Highland Railway system north of Inverness consisted of a line to Dingwall (18 miles) which then divided to reach Kyle of Lochalsh in the west (eventually) and Thurso/Wick in the north. Branches were constructed from Muir of Ord to Fortrose (opened 1894, closed to passengers 1951 and freight 1960), from The Mound to Dornoch (opened 1902, closed 1960) and from Wick to Lybster (opened 1903, closed 1944). West of Dingwall a short branch served Strathpeffer, a Victorian spa resort and while this enjoyed patronage in the early part of the century, it closed to passengers in 1946 and completely in 1951.

Space permits only a brief allusion to those lines which progressed no further than the planning stage. These were, on the Kyle line, an extension to Skye via a bridge, and branches from Achnasheen to Gairloch and Aultbea, and Garve to Ullapool. On the Far North Line branches were proposed from Bonar Bridge to Lochinver, Lairg to Laxford Bridge, Forsinard to Melvich, Thurso to Scrabster, Thurso to John o'Groats and Fearn to Portmahomack. In addition a branch from Conon to Cromarty was started with 6 miles of track and earthworks being laid down at the Cromarty end, but the outbreak of war in 1914 led to the abandonment of the project. Most of the proposals would have served areas with a very low population density and it is probable that freight, mainly in the form of fish and timber, would have accounted for much of the traffic on the lines. Even so, it is difficult to see how they could have succeeded, even before the advent of road traffic.

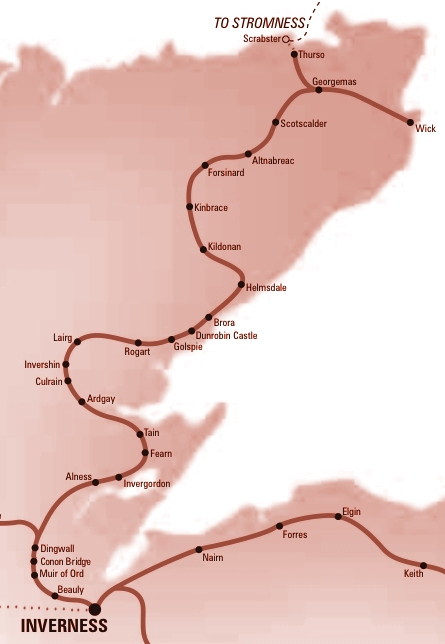

A glance at the map of the North of Scotland will reveal why the length of The Far North Line is approximately double that of the straight line distance. The topography is complex: there are three firths (Beauly, Cromarty and Dornoch) and other features such as the high ground to the north of Helmsdale known as the Ord of Caithness. For this reason the railway followed the much easier route through the beautiful Strath of Kildonan, leaving the fishing villages between Helmsdale and Wick isolated.

This is a map of the Far North Line which is situated in the northernmost part of Scotland. Hovering the pointer over the name of a station will display a local photo.

The line was built in stages from 1862 and finally opened all the way from Inverness to Wick in 1874. Forty-five stations were constructed along the route and of these only three were closed before the general rationalisation of 1960. The closures were based on a mileage-between-station basis rather than on likely passenger use and some sizable communities lost their station, such as Beauly, Conon Bridge and Evanton whilst at other smaller settlements the station was retained. In 1973 and 1976, respectively, the stations in Alness and Muir of Ord were reopened, and 2002 saw the reopening of Beauly station. Conon Bridge station was reopened in 2013.

The Far North Line is now a basic railway. The only staffed stations are Wick, Thurso and Dingwall, Brora losing its staffing in 1992. The line is signalled on the Radio Electronic Token Block System (RETB) controlled from Inverness. The consequent reduction in staff has been the most influential factor in the line's continued existence. At present, there are four trains each way per day plus a much improved Invernet service and an all year Sunday service of two trains in summer and one in winter. Improvements to connections to the South and East have been made. It is hoped that the Friends of The Far North Line will be able to press for more improvements to these services while at the same time ensuring the continued retention of the line by lobbying for the return of freight.